‘She’ll get hers’: VA hospital serial killer faces victims’ families at sentencing

CLARKSBURG, W.Va. – Norma Shaw is looking forward to her day in court Tuesday.

She and other relatives of veterans slain by a former nursing assistant at a Veterans Affairs hospital in West Virginia will finally have their say about what should happen to the serial killer who took their loved ones a few years ago.

The victims ranged in age from 81 to 96 and served in the Army, Navy and Air Force during World War II and wars in Korea and Vietnam. They died at the hands of the same person, at the same place, in the same way.

Reta Mays, 46, pleaded guilty last year to murdering seven elderly veterans with insulin at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center between July 2017 and June 2018. She also pleaded guilty to assault with intent to murder an eighth victim.

She is slated to be sentenced at the courthouse here Tuesday. She could get a life sentence for each second-degree murder charge, plus an additional 20 years for the assault charge.

Nurses who kill:Medical murderers and the mystery of the Clarksburg VA hospital in West Virginia

The proceedings are expected to include impact statements from Shaw and other family members, as well as arguments from the defense that Mays should receive less than life in prison.

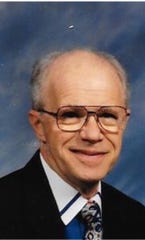

In March 2018, Mays was assigned to sit one-on-one with Shaw’s husband of nearly 59 years to monitor his vital signs during an overnight shift. Instead, she gave the Air Force veteran, who wasn’t diabetic, a lethal dose of insulin. His blood sugar cratered. Hospital staff scrambled to raise it, but George Nelson Shaw Sr., 81, lingered for nearly three weeks before dying.

“He hung on the longest of any of them. That was his will; he was so strong, he wanted to live,” Norma Shaw recalled in an interview Monday. “But he was just trapped in his body. He wanted to tell us something and he couldn’t talk, he couldn’t eat, he couldn’t walk.”

Air Force veteran George Nelson Shaw Sr., died on on April 10, 2018, at the VA hospital in Clarksburg, W. Va. His death, ruled a homicide by an Armed Forces examiner, is one of 10 under investigation by federal authorities. He was 81. (Photo: Family of George Nelson Shaw Sr.,)

His daughter Mary said she wishes Mays could receive a punishment equal to the suffering he and the others went through. Medical records show another victim struggled to breath as his blood sugar dropped, white foam oozed from his mouth and he faded away.

“Let her feel everything her victims felt but not die – the shutting down of organs, one by one by one by one,” Mary Wood said. “Daddy lasted two weeks suffering.”

“She’ll get hers,” Norma Shaw said Monday. She recorded a statement for the hearing, unsure if she would live to see it because she’s in poor health. But she’s going in person, along with Mary and her grandchildren.

Robert Kozul, 89, died January 30, 2018. Former nursing assistant Reta Mays pleaded guilty to killing him and six other elderly veterans with lethal doses of insulin at the U.S. Veterans Affairs hospital in Clarksburg, West Virginia. (Photo: Courtesy Kozul family lawyer)

The son of Robert Kozul, 89, said he simply wants answers.

“We have wondered and wondered and wondered about the ‘whys’ — why this happened and was able to happen,” James “Forrest” Kozul said in an interview.

His father, known to family and friends as Pappy, died in January 2018, the second of the seven murder victims outlined in court documents. “It shouldn’t have happened at all,” he said. “And then Dad. And nobody really realized the fact that this all was going on within the walls of the hospital, and it should have been caught.”

VA hospital murders ‘feel like a betrayal’

The Clarksburg chapter of the Fraternal Order of Eagles is down the street from the local VFW. At the members-only lounge, friends sit on leather chairs pushed up against an oval-shaped bar and chat about current events.

On Monday afternoon, that was the sentencing of Reta Mays.

Angela Insani is the daughter of an Army veteran who gets care at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center. What’s so frustrating, Insani said, is that veterans were victimized at the very place they thought they would be protected.

“She took a strike at the red, white and blue,” Insani said, her voice cracking. “She took a strike at America.”

Nearly two years after news broke about the insulin deaths, even after a global pandemic, the wounds remain fresh. That’s because the community has such a deep connection to the military, said local talk radio host Hoppy Kercheval.

“The story still resonates because it is so horrific, almost unimaginable,” Kercheval said. “West Virginia has a high rate of people who have served in the military, and many depend on the VA for their care. The murders at the VA hospital feel like a betrayal.”

VA inspector general to release report on what happened

After the sentencing, the inspector general at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is expected to release the results of an investigation into failings at the hospital that allowed the deaths to go undetected.

Mays was assigned to work overnight shifts on Ward 3A, the hospital’s medical surgical unit, in July 2017 when patients began suffering mysterious, acute drops in blood sugar.

A USA TODAY investigation in 2019 found that a string of oversights at the hospital may have cost veterans’ lives. Insulin wasn’t adequately tracked, and there were no surveillance cameras on Ward 3A. Staff didn’t conduct key tests to figure out why patients were experiencing severe episodes of low blood sugar. Nor did they file reports that could have triggered investigations.

This photo released July 14, 2020, by the West Virginia Regional Jail and Correctional Facility Authority shows Reta Mays. Mays, a former nursing assistant at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, W.V., is scheduled to be sentenced Tuesday, May 11, 2021, for her guilty plea to intentionally killing seven patients with fatal doses of insulin. (Photo: West Virginia Regional Jail and Correctional Facility Authority via AP)

Insulin can be crucial in keeping diabetics’ blood sugar in check, but for non-diabetics and those who aren’t prescribed the medication, it can be deadly, driving blood sugar too low.

By the time doctors alerted hospital leaders in June 2018 to the string of suspicious deaths, at least eight patients had died. Many had been embalmed and buried. One had been cremated.

How it started:Authorities investigating 10 suspicious deaths at VA hospital

Federal investigators zeroed in on Mays. They exhumed bodies and gathered evidence.

In July, Mays entered her guilty plea. She admitted to killing the seven veterans and administering insulin to an eighth who later died, too.

VA pledges improvements

The Department of Veterans Affairs said in a statement last week that the agency has made a number of improvements in response to the investigation by the inspector general, an independent watchdog. They include steps to increase care coordination between medical providers, bolster endocrinology referrals and evaluations and better train nursing staff on diabetes.

“The Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center grieves for the loss of each of these veterans and extends our deepest condolences to their families and loved ones,” the agency said. What happened “was unacceptable, and we want to ensure veterans and families know we are determined to restore their trust in the facility.”

The Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, W.Va., serves 70,000 veterans. (Photo: Donovan Slack, USA TODAY)

The Clarksburg VA draws patients from across the region, serving about 70,000 veterans in north-central West Virginia and nearby Maryland, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

In December, the VA replaced the hospital director and chief nursing executive and retrained staff on critical incident reporting after an internal review identified problems with patient safety. The hospital conducted a “safety stand-down” in which noncritical patients weren’t admitted for several weeks.

“People are satisfied now,” said John Aloi, senior vice commander of VFW Post 573 in Clarksburg.

Wearing a black “United We Stand” mask after wrapping up a Monday night meeting at the post, Aloi said veterans want a measure of justice from the court hearing. Equally important, he said, are safety reforms at the VA hospital.

“But the real test is how things go in the future,” he said. “Once you lose trust, it’s hard to get it back.”

Contributing: Ken Alltucker

Source: Read Full Article