Another one bites the dust: The neobank financial experiment that failed

As the last of the three true neobanks, Volt, disappears, it’s time to call it for what it is – the end of an unsuccessful corporate experiment.

It’s also a bit of a bloody nose for the regulator and its chair Wayne Byres who issued these three fintech lab rats – Volt, 86 400 and Xinja – with banking licences.

But Byres, who chairs the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has a softer, more palatable description of the result of the neobank experiment – “successful failure”.

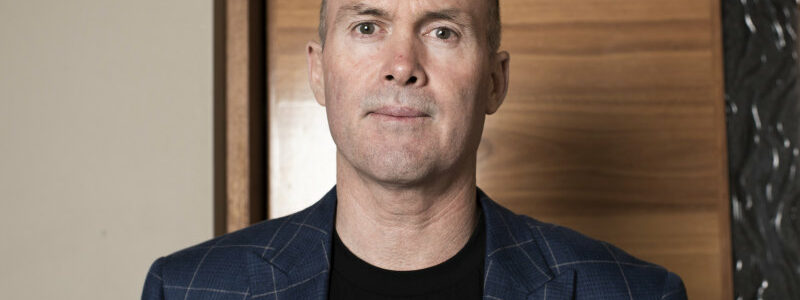

Chief executive Steve Weston will hand back Volt’s banking licence.Credit:Christopher Pearce

The inspiration behind the granting of additional banking licences appears to have been a response to the banking royal commission that aired criticism of a lack of competition for the big four.

The “success” measurement comes courtesy of the fact that the banks’ depositors didn’t lose any money and were repaid (or being repaid in Volt’s case) in an orderly fashion.

Investors in the neo banks – all of which have now handed back, or are in the process of handing back, their banking licences – haven’t all fared so well.

Those who had funded Volt and Xinja will walk away with nothing, while shareholders in 86 400 Ltd were luckier because it was bought and subsumed by National Australia Bank’s digital bank a year ago. Whether 86 400 would have survived independently never got tested.

While there was a fourth banking licence awarded to Judo Bank, lumping this organisation under the umbrella term of a traditional neobank is a mis-labelling.

Judo operates an entirely different model from the three that have handed back their licences. It is focused solely on the SME business market and rather than relying on technology to service clients digitally, Judo operated a “high touch, high take model”.

It was something of a curiosity in the industry because it offered a very personalised service to its business customers – harking back to the way the big four banks operated decades ago before they applied more of a cookie-cutter approach to small business lending.

It is run by 35-year banking veteran, Joseph Healy, who spent his career working at the major banks.

That said, the distinction is not clear to the market that punished Judo’s share price on Wednesday to the tune of 8 per cent on the back of the news that Volt’s battery had died.

The other big distinction between Judo and the rest is that it was able to raise sufficient capital to fund its operations. The others found it difficult to impossible.

These three neobanks are distinguishable because as holders of a banking licence they are able to collect deposits to fund operations. The downside is that they have regulatory capital requirements that are much larger than fintechs that don’t have a banking licence. Those without a banking licence need to find other means of raising capital -usually through wholesale financial markets.

Volt’s chief executive Steve Weston put the demise of his organisation down to its inability to raise money. “Capital raisings haven’t been easy, but they are doubly difficult in the current environment,” Weston told The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age on Wednesday.

He additionally lamented that there isn’t a mature venture capital pool in Australia that is needed to provide funding. And this is even though the neobanks had developed particularly sophisticated technology and products that were appreciated by customers and recognised by potential investors.

(Indeed National Australia Bank’s acquisition of 86 400 was about getting access to its technology more cheaply than developing it internally.)

In Volt’s case it had about $100 million in deposits and a mortgage book of roughly the same size. But to get to scale Volt needed $200 million in additional capital this year – a tough ask in a market that has shredded technology stocks.

It failed to raise those funds which would have been only the tip of the capital iceberg. Weston said even had this round of funding been successful, it would need to be backed up by an additional $1 billion-plus over the next few years.

The Market Recap newsletter is a wrap of the day’s trading. Get it each weekday afternoon.

Most Viewed in Business

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article