Inflation Rippling Through Markets Is Just What Fed Wants to See

Every new sign that U.S. financial markets finally see some inflation in the pipeline is another piece of good news for the Federal Reserve.

Bond-marketindicators of inflation, from long-term yields to the cost of hedging, have all pushed higher in recent weeks. Investors can see price pressures waking up — perhaps more than the U.S. is accustomed to lately, but well short of Fed targets, let alone anything that would set off alarm bells with the economy still stuck in a coronavirus slump.

Expansionary fiscal policy is helping to drive the change in outlook. That gives the central bank, which meets next week to discuss policy, another reason to cheer. It has struggled to gin up much inflation in the past decade with its own tools.

Heading into what looks like a monetary-policy gap year, with neither bond purchases nor benchmark interest rates expected to change in 2021, the Fed is far more worried about the risk of long-term scars — which could develop from a slow recovery — than about the risk of overheating the economy.

It’s been promising not to apply the brakes anytime soon –- and urging politicians to hit the accelerator with more pandemic stimulus. Joe Biden’s new administration is poised to oblige, by asking Congress for another $1.9 trillion.

‘Beginning to Work’

“This all suggests that what the Fed wants is beginning to work in the markets,” said Jim Caron, a fund manager at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, which oversees over $700 billion in assets. “Unlike in the past, when it pulled back policy when things were good, it’s now set to keep policy accommodative even in a recovering economy.”

Inflation has been below the Fed’s target for most of the past decade. Steady prices don’t sound like a bad problem to have, but central bankers and most other economists prefer a little inflation. It helps employers manage their wage bills, makes debt servicing easier, and allows interest rates to be set at levels that leave room for cuts in a downturn.

Under a new policy framework adopted last year, the Fed wants an average inflation rate of 2% over time –- which means it could tolerate a higher one for a while. Markets aren’t quite there yet.

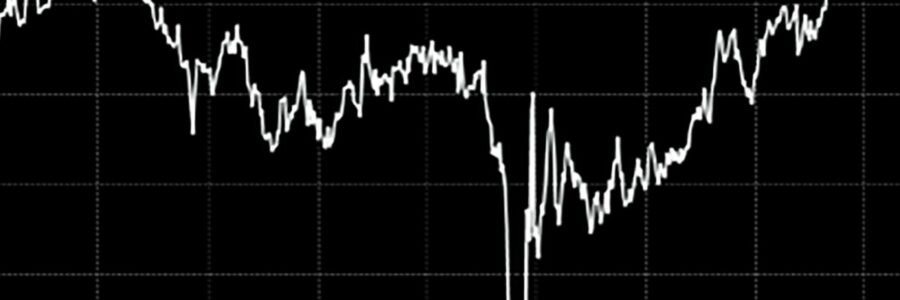

Five-year forward swap contracts on consumer-price inflation have risen above 2.3%, and currently hold just below the highest since 2018. Adjusting for measurement differences between CPI and the Fed’s preferred measure, that puts longer-run inflation pricing right around 2%.

The market is “only now pricing in inflation normalization, not even an overshoot,” said Michael Pond, global head of inflation-market strategy at Barclays. Even so, year-on-year price increases will likely be “above levels we have seen in many years because of very weak monthly readings last spring.”

‘Wages are Key’

Actual inflation has been low since the pandemic struck. Core consumer prices, excluding volatile food and energy costs, rose 1.6% in December from a year earlier.

Potential triggers of inflation include a surge in demand as Americans get vaccinated, though the Fed has signaled it will likely treat that as a temporary blip. There are forces pushing the opposite way too, such as lower rental costs in large cities. Above all, millions of would-be workers still haven’t recovered jobs lost in the pandemic, restraining consumer demand and meaning sellers of goods and services still have to compete hard on prices.

“To get actual inflation that leads to higher inflation, which is what central banks are vigilant against, you need wages to rise,” said James Athey, a London-based money manager at Aberdeen Standard Investments, which oversees assets of over $560 billion. “And with unemployment where it is now, I struggle to believe you are going to get wide-based wage growth.”

Athey sees expectations for 2021 as “overly optimistic” -– with regard to economic growth and virus containment –- and said he’d be a buyer if 10-year Treasury yields rise sharply again. They reached as high as 1.19% this month, the highest since the pandemic escalated across the country in March, but have fallen back a few points.

‘False Economy’

Ten-year breakeven rates, which measure the gap between yields on inflation-protected Treasury debt and the ordinary type, have climbed to the highest since 2018 at around 2.1%. Like other forms of protection against inflation, they’ve been attracting investors. JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategists are warning buyers that they shouldn’t expect to get rich quick.

“Breakevens, steepeners and gold are still appropriate inflation hedges for an inflation cycle that could break out of 20-year ranges eventually,” they wrote in a Jan. 15 note. But they’re unlikely to deliver large returns in the next year or two, when slack in the economy will cap any rise in core inflation to “a few tenths of a percent.”

If that kind of small increase no longer spurs Fed officials into tightening, one reason is the lessons learned after the 2008 financial crisis. Policy makers have broadly concluded that they withdrew support too early back then –- and are now inclined to err on the side of keeping the spigots open too long.

A similar attitude also applies to government spending, seen by the Fed as crucial for economic recovery and reflation. The point was made this week by Janet Yellen, who was in charge of monetary policy as Fed chair last decade and is now set to steer fiscal policy as Biden’s Treasury Secretary.

“We can afford what it takes to get the economy back on its feet, to get us through the pandemic,” Yellen told the Senate Finance Committee on Tuesday. “It would be a false economy to stint.”

Source: Read Full Article