On Brown v. Board anniversary, white Americans must still wrestle with legacy of racism

As we commemorate the 67th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education today, Americans have much to learn about the legacy and unrealized promise that Brown represents.

As a student of American history, a civil rights lawyer and an education equity expert, I thought I was well-versed in the landmark decision. A recent discovery about Brown humbled me and reveals something essential about why Americans are still so riven by issues of race and racism.

I grew up with reverence for Brown’s striking down legal segregation in public schools. I wanted to follow in the footsteps of Thurgood Marshall and advance America’s quest for racial justice.

Starting my career litigating education civil rights cases at the Justice Department brought new lessons about Brown’s legacy. In the late 1990s, there were still hundreds of active desegregation cases all over the South.

I saw shocking, squalid conditions in public schools, with the worst facilities serving mostly Black students. I learned about the fear and intimidation parents experienced advocating for their children’s rights. And I learned about the uneven burdens borne by Black families in the remedy — how historically Black schools were closed, decimating the ranks of Black educators and leaving abandoned buildings in their communities.

I held on, however, to the righteousness of the unanimous opinion in Brown. And it is still true that no other court opinion has invalidated such widespread rules on which society operated.

Reading Brown, it’s clear the justices wanted to be accessible and compelling to a lay person. Supreme Court opinions are often long and usually boring. But Brown is brief and appeals directly to the conscience of the nation, speaking in moral and practical terms about the role of schools in society.

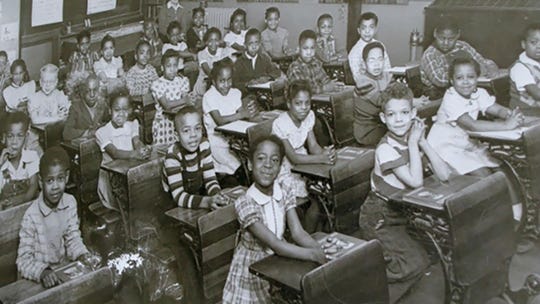

The Supreme Court’s decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case provided one of the first major victories of the civil rights movement. Oliver Brown sued the Topeka, Kansas, Board of Education, saying the city’s schools for Black students were not as good as those for white students. The justices ruled that the idea of public facilities being “separate but equal” was unconstitutional. (Photo: nps.gov)

The opinion famously relies on social science evidence submitted by Kenneth Clark and other eminent scholars establishing that segregation harms the psychological development of Black children, and that official segregation “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.”

Even as I revered Brown and its cause of vindicating the rights of Black Americans, it always struck me as necessary but not sufficient. The ruling talks about the harm of segregation to Black children, but I also wondered: Why weren’t we also addressing the toll racism takes on the psychological and moral development of white Americans?

Segregation also hurt white children

Only recently, reading Heather McGhee’s “The Sum of Us,” I learned that this argument was presented directly to the Supreme Court. The pivotal social science brief in that case explicitly speaks to the damage to the moral character development of those who are ostensibly privileged by segregation.

As white children were “taught to gain personal status in an unrealistic and non-adaptive way,” the social scientists warned, they “often develop patterns of guilt feelings, rationalizations, and other mechanisms, which they must use in an attempt to protect themselves from recognizing the essential injustice” and feeling “moral cynicism” at the contrast between what they are taught about America and what they observe.

The justices ignored this rationale, leading desegregation remedies to be conceptualized exclusively as doing something for Black children.

There can be no doubt that segregated schools and the whole edifice of Jim Crow hurt Black Americans most. However, the legal, social and psychological structures that sustain systemic racism stunt the moral development of white Americans, imbuing this country with a racial hierarchy that is at odds with our professed ideals.

Ross Wiener is executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Education & Society Program and a former trial attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice. (Photo: submitted photo)

Where would we be today if the justices had been willing to name the harm segregation does to the psychological and moral development of white children, too?

States restrict teaching about racism

We are now at another crossroads in America’s journey toward redemption. Students are living through a profound teachable moment regarding race. And yet state legislatures around the country are trying to silence efforts to address and educate students about systemic racism, even threatening to fine teachers for engaging students with “controversial” topics.

How will these decisions impact future generations? While Heather McGhee speaks in terms of the economic costs, we must also acknowledge the moral and psychic costs, too.

White Americans must own-up to the ongoing injury racism creates, and the broken society it bequeaths to our children; we cannot frame the work only by what is owed to Black Americans.

In this next year, I hope white Americans engage in learning and self-reflection to approach reconciliation with an open heart. Soon, it will be a year since George Floyd’s murder, a century since the Tulsa Race Massacre, 155 years since Juneteenth — all within a month of Brown v. Board’s anniversary.

Grappling with racism’s enduring harm on our moral and ethical development can move us toward the just and equitable society to which we aspire but has painfully eluded us thus far.

Ross Wiener is executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Education & Society Program and a former trial attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to [email protected].

Source: Read Full Article