She Survived a Helicopter Attack and Gave Birth in Office: Now Tammy Duckworth Writes 'Love Letter' to America

Illinois Sen. Tammy Duckworth says her new book, Every Day Is a Gift, started with a question from her young daughter.

"Abigail had been asking me why I went to Iraq and why was I willing to lose my legs, because now I couldn't run with her and I wasn't like the other mommies," Duckworth tells PEOPLE.

"How come somebody else's mommy or somebody else's daddy could've gone and lost their legs instead of me?" the Iraq War veteran, whose helicopter was shot down in 2004, remembers her 6-year-old asking one day.

So Duckworth, 53, started jotting down notes.

Flying again between Washington, D.C., and her home state of Illinois, she took down memories on the notes app on her phone or wrote on anything else she could find, making a list of the harrowing details of the life she wanted one day sit down and share with Abigail and her 3-year-old, Maile.

"I was just sort of jotting down things that I'd want to talk with her about when she got older, that would be my explanation why America is worth it," Duckworth says.

"Before I knew it, I had enough for a book proposal" — her first.

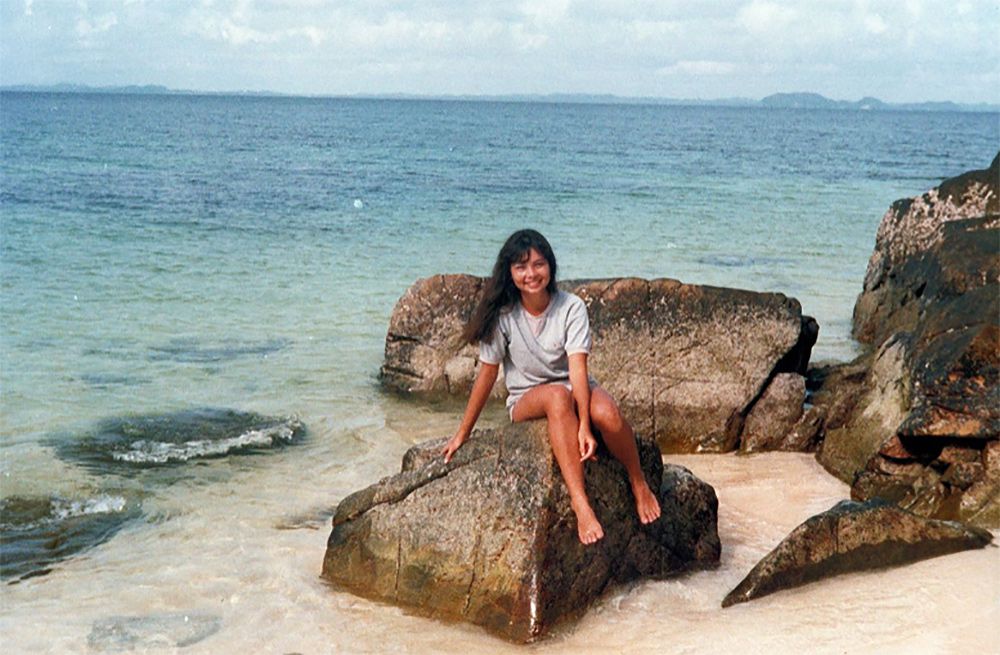

What she wrote down during whatever small down time she could find as a U.S. senator wound up being the first draft of Duckworth's life story in her own words. It's a journey that started in Bangkok as the biracial child of a U.S. marine from Virginia and a Chinese-born souvenir shop owner who found a new life — and love with an American soldier — in Thailand.

But nothing ever came easy, the senator writes in her biography.

"I hated being teased and feeling different," Duckworth recalls about her childhood, between stories about getting made fun of by her Thai cousins for being biracial and an older brother, Tom, who seemed to get all of their father's attention.

In her memoir, Duckworth describes life in a military family always on the move: Bangkok, to Cambodia, back to Bangkok, then to Hawaii and all the way to D.C. before landing in northern Illinois for graduate school.

There were close calls: Duckworth was not yet 7 years old when she and her mother, Lamai, hid underneath windows at a Cambodian airport to avoid the bullets overhead, waiting to board the last flight out of a country in civil war.

When she, her brother and father Frank eventually moved stateside, to Hawaii, the teenager became the family's breadwinner. On the heels of odd jobs handing out flyers and selling roses, she helped keep food on the table and rent paid.

"We were broke, had no place to live and were on the brink of homelessness," Duckworth writes of those early days in Honolulu, where she went to high school and "was constantly pushing myself to be better, smarter, and stronger" to win her dad's affection.

She filled in her family's financial gaps while her dad was out of work. She became a student-athlete in discus, just like he did, and learned from him how to change the oil on a car. Most of the time, a young Duckworth felt, all she received in exchange was little affection and slim attention.

Writing her book now, decades later, helped Duckworth see her family dynamics more clearly, she says.

"I was better able to come to terms with my relationship with my dad and the fact he was not the superhero I thought he should've been when he was younger," she says. "He was a man, like anyone else, with his flaws — but he was there for us our entire life. He never abandoned us."

The book's most gripping moments, of course, surround the injuries she suffered in 2004 as an Army helicopter pilot who was shot down in Iraq.

Life up to that point was something of an "inoculation" to what she survived in the helicopter attack.

"As I wrote the book and got into the later chapters, I started looking back and I went, 'Wow, I didn't think of myself as having gone through a lot, but apparently I did,' " Duckworth explains. "Maybe that's why I was able to survive being wounded as well as I was."

A rocket-propelled grenade took down the black hawk helicopter Duckworth was co-piloting. She lost of both of her legs and suffered severe damage to her right arm.

In her memoir, she recalls the pain of her recovery at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in near-overwhelming detail: "It was relentless, dizzying in its force, nauseating. My legs and arm were on fire, inside and out, and the rest of my body just hurt, over every square inch of me. Even my hair follicles hurt."

"I'm always grateful my husband was there for me," Duckworth says now of Bryan Bowlsbey's near-constant presence at her bedside. (Her mother also sat in anytime Bowlsbey, a retired major in the Army National Guard, had to step away.)

Bowlsbey, too, took notes during her recovery and his recollections are interspersed in the chapters about her injuries to fill in her unconscious gaps.

Now, as the two-term senator is writing down her own story, she is increasingly playing a bigger role in the country's.

Duckworth, who in 2018 became the first senator to give birth in office, drew much notice last year after she made the final cut in President Joe Biden's search for a vice president, second only to Vice President Kamala Harris — "my girlfriend," Duckworth says of her former Senate colleague.

And though a memoir is a customary step on any politician's pre-campaign checklist, Duckworth says "no, no" — she doesn't have presidential aspirations down the line.

"That's a unique fire in your belly," she says.

"My life, as improbable as it is, could never have happened if I was not an American," Duckworth says. "The book is really a love letter to my country and an explanation to a question my daughter asked about, 'Was it worth it?' And my answer is yeah, it was. America is worth it."

Source: Read Full Article