Supreme Court rejects retired officer's bid to curb legal immunity for police

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday denied the appeal of a retired federal agent seeking to challenge sweeping legal immunity for police officers after he was injured during an arrest and later blocked from suing for damages.

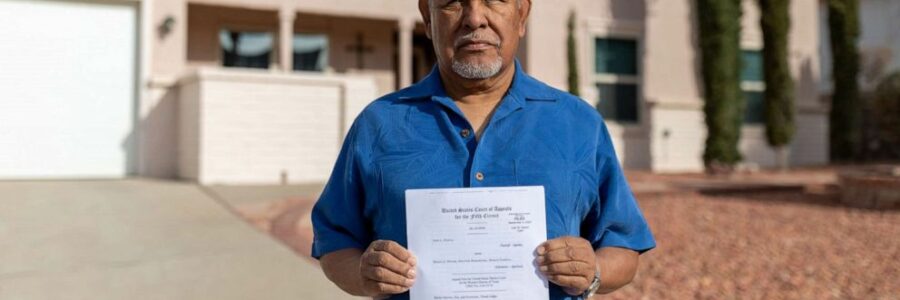

“This big guy grabbed my left hand and with his two hands, he jerked my arm as high as he could. Almost simultaneously, as this guy was jerking my arm, he put a chokehold on my throat very hard, very hurtful,” Jose Oliva, 76, said of the 2016 incident at the El Paso, Texas, Veterans Administration hospital. “I told them I can’t — I cannot breathe, let me go. I cannot breathe.”

Oliva, a Vietnam War veteran and longtime VA patient, underwent two surgeries to repair injuries he sustained. A federal appeals court rejected his bid to sue the officers for damages.

The Supreme Court’s decision to let that ruling stand — the latest in a string of police immunity cases it has refused to take up in the past year — suggests the justices are not eager to wade into a hot national debate over law enforcement and legal protections for officers that the court itself helped construct.

Qualified immunity, a legal doctrine established by the Court 50 years ago, affords officers broad protection against personal liability for constitutional violations in most cases. Oliva’s case also sought to challenge the added protection against civil rights lawsuits that federal officers enjoy under federal law.

While Congress expressly allows civil lawsuits against state and local law enforcement officials, it did not create a legal avenue to pursue claims against federal officials. Since 1971, the Supreme Court has sharply limited the right of Americans to sue federal employees for damages under the Constitution.

“It’s a double high bar. It is a double protection,” for federal officers, said UCLA law professor Joanna Schwartz, a leading expert in qualified immunity.

“Qualified immunity protects officers, unless the plaintiff in the case can find a prior court decision with virtually identical facts, holding those facts and officer conduct unconstitutional,” Schwartz said.

Accountability for federal officers has drawn special scrutiny after last summer’s protests for racial justice when legions of federal agents — many unidentified — performed policing functions in major cities across the US in roles normally left to state and local agencies.

“Not only are there more federal agents and special agents and officers, but they are doing more in the way of policing than has typically been the case with regard to our historically very limited federal police apparatus,” said Seth Stoughton, a former police officer and law professor at the University of South Carolina.

In 2000, there were 88,000 federal law enforcement officers, most working in Customs and Border Protection or the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Today, they number more than 132,000, according to the Justice Department.

Law enforcement advocates say qualified immunity and other legal protections are essential to preventing harassment of officers, potential financial ruin, and psychological distraction when working in dangerous situations.

“That way they can do their job and not have to be second-guessing, ‘Am I going to let this guy through? The last time I did, I got sued. I’m not going to take the chance,’” said Louis Lopez, a Texas attorney representing two of the officers in Oliva’s case, Mario Garcia and Hector Barahona.

“We don’t want to have our frontline security officers having to make these type of legal decisions when they’re in life or death situations or circumstances,” Lopez said.

But critics say the data doesn’t back up claims of widespread impact on officers if immunity was rolled back or lifted entirely.

“I spent five years as a cop. I tend to trust generally in the professionalism of other officers, and I find it very infantalizing when someone says that concerns about possible prospective lawsuits — purely speculative lawsuits — are going to be so strong that those fears are going to keep an officer from doing their job,” said Stoughton. “I just don’t buy that.”

The physical altercation involving Oliva, captured on VA surveillance video, shows officers forcefully taking the 70-year-old into custody following a verbal dispute near the hospital magnetometer. The recording did not capture audio of the conversation.

“The officer asked for me ID… I told them my VA card, my ID is in the bin,” Oliva recalled, “and for whatever reasons, he did not like that answer.” The officers, who dispute that account, cited Oliva with disorderly conduct; the charge was later dismissed.

“The lack of audio is telling,” said Gabriel Perez, a Texas attorney working with Lopez on the case. “Just because something happens on camera doesn’t mean there isn’t a verbal altercation that leads up to that.”

“You can’t look at this one isolated incident in a vacuum,” he added. “In 2015 in El Paso, at the same facility, there was a shooting there.”

Lopez said the officers’ use of force was aimed at neutralizing a potential threat.

“They don’t know if Mr. Oliva has dynamite strapped to his chest or he’s got a 45 handgun that he’s going to just start shooting people indiscriminately,” said Lopez.

Oliva’s attorney, Patrick Jaicomo with the Institute for Justice, insists the use of force was excessive and unjustified. “There’s just no way any reasonable person can watch that video and think that there was any reason for those VA police to do what they did to Jose,” he said.

For many victims of alleged police abuses, civil claims are the only avenue for justice after injuries sustained at the hands of cops. And qualified immunity is a major sticking point, advocates say.

A Reuters investigation last year found police won 43% of federal excessive force cases between 2014 and 2017 when invoking qualified immunity. Over the next three years, it increased to 56%.

It’s a trend some say underscores the need for reform.

“The Supreme Court talked about it as a good faith defense when the officers believed that what they were doing was constitutional, that there should be some manner of protection,” said Schwartz. “But the Supreme Court’s desires to protect more and more officers has led them to create a standard that is more and more difficult to meet.”

Negotiations in Congress over a sweeping police reform bill in honor of George Floyd are now stalled over whether to eliminate qualified immunity.

“There are big policy trade offs when you have an immunity for government officials,” said law professor Christopher Walker at The Ohio State University. “If you look at the legislation that the Congress is considering, some of it doesn’t get rid of qualified immunity entirely, it only narrows it.”

Even though the Supreme Court declined to take Oliva’s case and set a new national standard, more than two dozen states are considering their own limits on legal immunity for cops.

“The qualified immunity is basically too broad,” he said. “It’s not specific.”

Source: Read Full Article