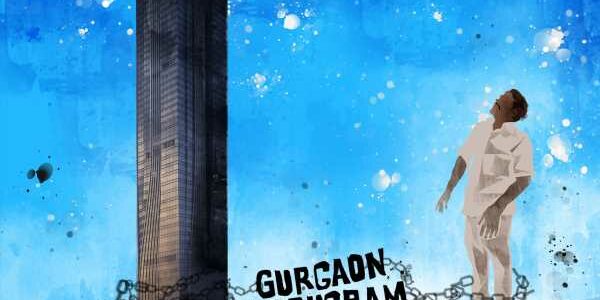

Is Gurugram going the Kolkata way?

Militant labour policies compounded a poor security environment for capital in West Bengal and encouraged the business community to relocate. constraining the private sector’s right to hire freely could well be the coup de grace. As with Calcutta/Kolkata, it will probably take a decade for Gurgaon/Gurugram to feel the difference, says Kanika Datta.

Gurgaon, the city that accounted for a significant amount of Haryana’s GDP long before it became Gurugram, is unlikely to see an immediate mass exodus of businesses following the notification of this troublesome law mandating 75 per cent of locals in private enterprises from January 15 next year.

That’s because the law applies to new hires earning up to Rs 30,000 and having lived five years or more in the state.

But with the example of another vibrant metropolis that declined on the back of a headlong flight of capital, Calcutta before it became Kolkata, it is possible to imagine a similar future for the millennium city from here on.

Militant labour policies compounded a poor security environment for capital in West Bengal and encouraged the business community to relocate, taking with it that unique progressive multiculturalism that is feted nowadays in a thriving cottage industry of nostalgia on social media.

Labour policies in the shape of a new hiring law is likely to provoke a similar exit of capital from Gurgaon.

The development of Haryana’s golden goose has thrived despite reflecting all the worst contradictions of post-liberalisation India.

It isn’t the state capital but it is certainly its principal city, contributing the bulk of the state’s revenues.

Its proximity to the National Capital and the booming real estate expansion led by DLF created a bustling metropolis by default.

Here, where decent-sized property could be acquired without the cumbersome power-of attorney route and sky-high costs of a New Delhi realty deal, foreign companies set up their back offices and IT-enabled services hub to serve geographies many time zones away, creating the beginnings of the bustling, chaotic urban agglomeration.

Unlike the well-planned, well-lit, manicured Noida, the eastern extreme of the area designated the National Capital Region, Gurgaon offered a view of the extremes of new India.

Singapore-style glass and concrete structures soared on roads that reflected Gurgaon’s recent status as a village.

Grid power remains so problematic that no self-respecting facility comes up without a generator.

Near non-existent public security has meant that exclusionary gated communities pushing up against the slums whose denizens serve them have become the leitmotif of the city.

Yet, against the odds, unlike orderly Noida or the functional discipline of Chandigarh, it’s Gurgaon that attracts the big names from around India and the globe, recording more foreign presence per square km — corporate and residential — than any other city in India.

Migrants from all over India crowded in for jobs from the most menial to most sophisticated, adding to its dynamism.

That has brought in its wake the boom in goods and services.

Where upscale restaurants first opened in Delhi and then followed with Gurgaon branches, the sequence is often reversed now.

This fin de siècle scenario is very much a pre-Covid-19 phenomenon.

Today as the glittering facades of Cyber City echo with the emptiness of employees still working from home, malls struggle to attract footfalls and massive towers along the newer reaches of the city lie empty, stoking jobs and demand should be the first thing on the mind of the state government.

Yet two months ago, Haryana chief minister claimed his state does not have an unemployment problem.

Combating CMIE’s data that showed an unemployment rate of 35.7 per cent for the state, Manohar Lal Khattar claimed the correct figure was 9 per cent.

And if, according to him, the fact that many employed youth registered on the exchanges for better jobs, the real number would be 4-5 per cent.

So if there is no employment problem as such, then the labour reservation imposition on the private sector is redundant.

If it is aimed at Jat youth who have been demanding inclusion in Other Backward Class to gain government jobs, it is even more pointless.

These youth, erstwhile agriculturalists facing diminishing returns from shrinking land inheritances, are unlikely to work in the factory, clerical, wait-staff or menial jobs implicit in the salary cut-off of the reservation law.

Still, any new outfit setting base in the state or one that’s looking at expanding will have to waste time trying to find locals to fill these jobs or convince a state inspector that they cannot find them.

When Gurgaon’s weak infrastructure is factored in, the attractions of Delhi and Noida as attractive alternative options will suddenly grow.

Worse, when the policy will inevitably make little difference to local employment, expect riots of the kind that saw Indian citizens from the east fleeing Mumbai and Bengaluru not so long ago.

Gurgaon has suffered the depredations of state government policy in the past.

In the late nineties, it was prohibition that cost the state so much revenue that it brought down a government.

In the early noughties it was a chief minister who appropriated Gurgaon’s revenues for his own constituency, which cost the city decent civic infrastructure.

Somehow, none of this made a material difference to the hectic pace of corporate activity.

But constraining the private sector’s right to hire freely could well be the coup de grace.

As with Calcutta/Kolkata, it will probably take a decade for Gurgaon/Gurugram to feel the difference.

Source: Read Full Article