‘Just cruel at this point:’ Nursing homes pushed to reopen for visits, hugs after Covid vaccine

A Missouri man worried about his mother’s weight loss after she spent a year in a nursing home under COVID lockdown without his daily peanut butter shakes.

In Florida, a devoted husband celebrated his final wedding anniversary on opposite sides of his wife’s nursing home window.

A woman in the Bronx, New York blamed her recent mild heart attack on stressful months of separation from her mother.

“I couldn’t hug her for Mother’s Day, for the whole year,” Lillian Marrero said.

The residents of America’s nursing homes and assisted living facilities, the first and hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, now offer early evidence of the vaccine’s power to end the threat. Outbreaks in nursing homes have dropped by about 90 percent since the winter’s peak, with their residents and staff placed at the front of the line for vaccination.

CDC: Nursing home residents added to first phase of COVID-19 vaccine rollout

Government regulators this week mapped out how nursing homes can reopen to visitors more widely, a year after abruptly closing their doors. The full toll on the elderly and frail inside is only beginning to come to light.

Grassroots advocates have lobbied the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to ease restrictions intended to protect against a virus responsible for more than one million cases among nursing home residents and staff and at least 131,700 deaths. Those numbers do not capture what happened in assisted living facilities or the physical and mental consequences of isolation.

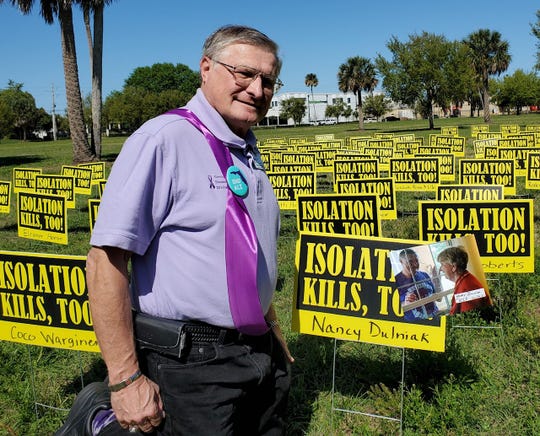

Over the past week, black-and-yellow posters have been on display in cities nationally as advocates pressed for greater access to loved ones in nursing homes and, ultimately, reforms to give them more say in future decisions. Their pointed message: “Isolation Kills, Too.”

“The cure for protecting these seniors could be worse than actually getting the COVID,” said Vivian Rivera Zayas, who co-founded Voices for Seniors when her mother died after she contracted the virus in a New York nursing home. “They are protecting them to death.”

The director of the CMS nursing homes division, Evan Shulman, said he has heard from residents who would rather die of COVID-19 than go any longer without seeing family.

“The second most heartbreaking thing about this pandemic, right after deaths, is the toll that the separation had taken on residents and their families,” he told advocates on Friday during a webinar discussing the new guidance.

The eight-page memo says nursing homes “should allow indoor visitation at all times and for all residents.” The federal guidelines also let people get close enough to touch, saying “there is no substitute for physical contact, such as the warm embrace between a resident and a loved one.”

There are some exceptions related to unvaccinated residents, how many within a facility have received vaccines and signs of a new outbreak.

Details already are drawing concern that facilities can continue to limit the daily, hands-on access that families used to get as a matter of right. For example, advocates fear permissive words like “should” rather than “must” could be exploited as loopholes.

USA TODAY is investigating the COVID-19 crisis in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. If you or your loved one experienced problems during the fall or winter outbreaks with the safety and rights of a resident, please contact Letitia Stein at [email protected]

They also worry about whether the rules will be enforced. In its webinar with CMS, officials with the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care noted states and facilities were allowed to ignore previous federal guidance supposed to give families more access.

Robyn Grant, director of public policy and advocacy, said restoring close contact like hugs is a welcome step, but families think “there is still a long way to go.”

The more than 14,000 nursing homes and assisted living facilities represented by the American Health Care Association “cannot wait to safely reopen,” President and CEO Mark Parkinson said in a statement.

Federally supported advocates for nursing home residents in each state also are eager for the latest guidance to clear their path back in.

In recent weeks, they have been sharing stories like that of the Michigan man who stopped eating and refused to get up, trying to fake his own imminent death to qualify for a family visit. An Ohio woman told her state’s long-term care ombudsman she wanted to learn how to hold an unlit cigarette in her mouth, because her facility gives smokers outdoor time.

“Many residents have said they feel like prisoners,” said Mark Miller, president of the National Association of State Ombudsman Programs. In most states, he noted, representatives have spent the year locked out of facilities they would routinely visit to monitor conditions and assess complaints.

The result has contributed to a nearly 20 percent decline in the complaints logged last year into the Washington D.C. ombudsman office that Miller directs.

Nursing homes did not have fewer problems, advocates fear, just fewer eyes and ears inside to spot them.

“When the cat’s away, the mice play. There has been a lot of playing going on,” said Brian Lee, executive director of the Families for Better Care advocacy group. “Unfortunately, that has been bad for the residents.”

Unpredictable rules spread with pandemic

Exactly one year ago, the lives of families like the Florida Dulniaks were upended by the unpredictable and still evolving rules imposed in response to the dangers of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities.

On March 12, 2020, a sunny Thursday, Dennis Dulniak said good-bye to his wife, Nancy, after snapping photos of her smiling in her room, as he did to document their daily visits for two adult sons who live out of state. He barely saw her again for 28 weeks.

By the next day, CMS would issue guidance to curtail nursing home visitation. Assisted living facilities like the memory care community where Nancy Dulniak lived near their home in the central Florida town of Oviedo fell under similar restrictions by governor’s orders.

Dennis Dulniak spends time with his wife, Nancy, on September 22, 2020 at her assisted living facility in Florida under provisions allowing for compassionate care visits during COVID-19 at long-term care communities under shutdown orders. (Photo: Courtesy of Dennis Dulniak)

The swift actions came after the nation’s initial COVID-19 outbreak ripped through a nursing home near Seattle, foretelling how vulnerable such institutions would be.

For Nancy, then 68 years old and six years into a diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, it was the beginning of the end.

Long-term care residents could stay connected with loved ones by phone or video streaming but Nancy found the technology confusing. Her husband cannot recall a single good virtual conversation.

A bright spot: A window visit in early June to celebrate their 47th wedding anniversary. For an hour and a half, despite a noisy road and reflections in the glass – which restricted not just airflow but also easy conversation – Nancy locked eyes with her husband.

From opposite sides of the window, each enjoyed spoonfuls of her favorite frozen custard.

As the nation eased up on COVID-19 lockdowns, her facility started organizing drive-thru visitation. Nancy could not place her husband’s masked face behind a car window, not even when he waved a balloon and a poster reading “Nancy, I love you. Dennis.”

CMS tried to clear up confusion about how caregivers could safely see loved ones in nursing homes with guidance updates. By September, the agency indicated that nursing homes in communities with reasonably controlled COVID rates should be allowing visits, although there were still many limitations.

Florida by then had broadly reopened for business, but visitation was still nowhere near normal at long-term care communities, which had latitude to restrict how many visitors were allowed at a time, how long they stayed and protective gear precautions.

At Nancy’s facility, the options continued to be problematic. She struggled to communicate with her husband from a distance of six feet at a dining room table, where he had to wear a plastic shield and a mask over his face.

CMS also had detailed circumstances allowing for “compassionate care” visits, which included when residents showed signs of mental or physical deterioration. This is how for about a month, Nancy saw her husband in her room twice a week at 11 o’clock for an hour. He brought a laptop and played music they once enjoyed live. She called him by his name.

Then in October, Nancy tested positive for COVID. Though her symptoms were never severe, an outbreak ravaged her facility. She was evacuated. Her husband watched from the parking lot as she walked to a stretcher, then was loaded into a medical van.

Three weeks passed before he saw her again for a 30-minute outdoor visit. Nancy sat in a medical recliner. He spotted signs of bed sores on her feet. She pulled in frustration at the mask she was supposed to wear.

On January 26, a week and a half after moving Nancy to a new facility for better care, she took her final breaths. Her husband wasn’t there; he was down the hall from her room, awaiting a required COVID test.

He finds comfort that he was in the facility’s library when Nancy, a librarian, died alone.

This week, Dennis Dulniak helped set out a poster display in Orlando to call attention to stories like the couple’s. He wants stronger protections for nursing home residents’ visitation rights in future emergencies.

.

Restrictions during COVID, he said, “robbed me of my access to her.”

Dennis Dulniak stands beside a photograph of his wife, Nancy, at a display of posters reading “Isolation Kills, Too” in Orlando, Florida this week. He is campaigning for nursing home visitation rights following her death earlier this year. (Photo: Courtesy of Dennis Dulniak)

Enforcement of visit rights lacking

At another Florida assisted living facility, a woman made national headlines in July by taking a job as a dishwasher so she could see her husband. Mary Daniel then channeled the attention into a grassroots push to help caregivers navigate the maze of uneven, irregularly enforced state and federal rules.

She started a Facebook page, Caregivers for Compromise, now with more than 14,000 followers and has spun off separate groups for every state. “There is no consistency to what is happening out there,” she said.

Families for Better Care and other advocates have continued to hear complaints from multiple states about nursing homes refusing to follow the previous CMS guidelines on visitation rights. Enforcement has been lacking.

CMS did not respond to questions from USA TODAY this week asking about visitation concerns and enforcement, beyond sharing a press release with the updated guidance.

States have some discretion to limit visitation for health and safety reasons, the agency’s nursing home division director acknowledged on Friday’s webinar, and need time to react to new guidelines.

“We expect this to be implemented,” said Shulman, noting that times have changed since CMS’ previous update on nursing home visitation came out just before a fall and winter surge of outbreaks.

Southern Pines nursing home resident Shirley Campbell visits with her daughter, Margie Price, and son-in-law, Ken, through a glass door in Warner Robins, Ga., on June 26. (Photo: John Bazemore/AP)

At the start of February, Lee at Families for Better Care wrote to the agency asking for details about when and how nursing homes already well into vaccination campaigns could expect to get back to pre-pandemic visitation.

Three weeks later he received an emailed response, reviewed by USA TODAY, that did not answer his questions. An unsigned note from the agency’s nursing home division said: “I can assure you, we are eager to have residents reunited with their families, friends, and loved ones.”

Another two weeks passed before the agency updated its guidelines this week. Lee hopes it will push open the doors at facilities still resisting visits, although he notes it only applies to nursing homes, with assisted living facilities left to state authorities.

It still stops short, however, of saying when families can expect a return to normal.

“Our rights are not really being enforced,” said Jeff Stephens, who has now gone a year without a visit with his mother in a Missouri nursing home. He feared window visits would do more harm than good for a 78-year-old suffering from dementia.

Stephens said repeated requests for compassionate care visits went nowhere. Keeping him out all year did not protect his mother from contracting COVID either, although she did recover.

As of Friday, despite the new federal guidance, he had not heard anything about doors reopening directly from her nursing home in Cape Girardeau, an hour and a half south of St. Louis. He worries the facility can still limit visitation inside her room, even though being in a familiar setting matters with conditions such as dementia.

“I am anxious at this point,” he said. “I don’t know what to expect when I go back in.”

A “cruel” wait as states review rules

To some families, every additional day of waiting feels like an unacceptable delay.

In the Bronx, Marrero was crushed earlier this month when a staff member at her 84-year-old mother’s nursing home responded to her email asking to resume visits by noting that it could take another year to fully study the vaccine.

A window visit this week showcased how much her mother has declined. Before the shutdown, Hilda Torres still walked so briskly she was considered a flight risk. Now she uses a wheelchair.

“She is not responding, she is not talking,” Marrero said. “It is heart-breaking.”

San Vicente de Paul Skilled Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, where her mother resides, held a party on Friday to celebrate the milestone of getting 75% of residents and staff fully vaccinated. Administrators distributed $100 bonus checks to staff, calling the accomplishment notable in a facility whose residents and staff come mostly from Black and Latino communities in which experiences with discrimination have contributed to distrust of the vaccine’s safety.

Lillian Marrero visits with mother Hilda Torres, a resident of a nursing home in the Bronx, New York on November 17, 2019, before facilities were locked down in an effort to guard against the spread of COVID-19. (Photo: Courtesy of Lillian Marrero)

Officials at the facility run by the Archdiocese of New York’s health care system, ArchCare, want to open to visitors, but said they still need state permission in addition to the CMS directive. State rules as of this week told facilities to close for at least two weeks when someone tests positive. Physical distancing requirements conflict with the newly relaxed federal standard allowing hugs.

“The fact that family members have been more than a year without being able to see their loved ones, it is cruel at this point,” CEO Scott La Rue said. “Every day matters.”

The New York State Department of Health said it was reviewing the new CMS guidance.

The day after its release, Marerro once again visited her mother through a window. As she and other relatives said their good-byes, her mother cried. Marrero left in tears, too, but holding out hope they will soon be able to hug again.

Letitia Stein is a reporter on the USA TODAY investigations team, focusing primarily on health and medicine. Contact her at [email protected], @LetitiaStein, by phone or Signal at 813-524-0673.

Source: Read Full Article