Marianne Carus, Whose Cricket Magazine Reached Young Readers, Dies at 92

Marianne Carus, the German-born, Sorbonne-educated founder of Cricket, the lively and erudite monthly magazine often called “The New Yorker for kids,” died on March 3 at her home in Peru, Ill. She was 92.

Her death was confirmed by her daughter Inga Carus.

Ms. Carus (pronounced CARE-us) began Cricket in 1973 after years of dismay over what she considered the sorry state of children’s reading material, including the books that her own three children brought home from school.

“Good literature is literature you cannot put down,” she explained in a 2018 interview for the library at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. “And children for some reason did not get the best literature in the schools or in their homes.”

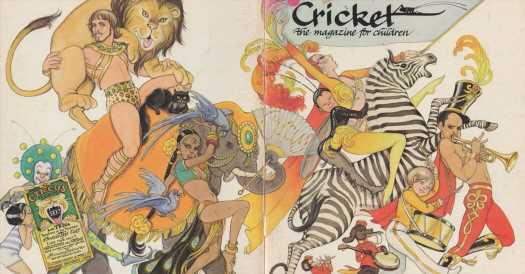

There were other magazines aimed at children in the 1970s, including Highlights and Ranger Rick, but Ms. Carus considered them insubstantial and condescending. She cut Cricket from finer cloth: It came bound like a paperback book, with enchanting hand-drawn covers labeled with the volume and issue number; inside, not a single ad interrupted the flow of fiction, biographies and science stories.

“Only Cricket seems to fly out of the mailbox straight from neverland, trailing clouds of something special,” the children’s author Jane Langton wrote in The New York Times in 1974.

The magazine blended serious literature with childhood frivolity: A story by John Updike could be followed by a comic strip, or a poem by Nikki Giovanni could come after knock-knock jokes.

Lest it still be confused with the The New York Review of Books, Cricket’s art director, Trina Schart Hyman, filled its margins with characters like Fat Ladybug, Ugly Bird and a know-it-all cricket named Cricket, who commented on the stories and explained challenging words.

The magazine was an overnight success, with more than 250,000 subscribers after the first year. Though that number subsided over time, Cricket maintained an intensely loyal following, as evidenced by the overflowing bags of fan mail and submissions to its art and writing contests.

Like Ms. Carus, the typical Cricket reader was intelligent and urbane, often far beyond his or her preteen years, and felt constrained by a culture that in the 1970s still relegated children to the edges of adult life.

“In the summer I write and edit a newspaper,” one 9-year-old correspondent wrote in a letter to the editor. “To my readers I say Cricket is the No. 1 magazine for children. I hope I give you some more readers. Good luck.”

While there was a good deal of fun to be had in the pages of Cricket, there was never a doubt about Ms. Carus’s faith in the nurturing capacity of big words and richly told stories.

“So many people talk down to children, but you have to respect their intelligence,” she said in an interview with The Baltimore Sun in 1982. “Parents give them the best clothes, the best food, the best toys, when what they should be giving them is food for their little brains.”

Marianne Sondermann was born on June 16, 1928, in Dieringhausen, Germany, and raised in nearby Gummersbach, about 30 miles east of Cologne. Her father, Dr. Günther Sondermann, was an ophthalmologist; her mother, Elisabeth (Gesell) Sondermann, was a nurse.

Dr. Sondermann was drafted as a medical officer in the German Army during World War II. Marianne served, too: In late 1944 the children in her high school were sent to the Western Front, where the girls cooked food and the boys dug trenches — a searing experience that colleagues said later shaped her vision for Cricket.

“Like many of us in this field, Marianne’s childhood was strongly with her, and her motivation was to create a world for children far removed from the fear and worry she must have experienced,” Jean Gralley, one of the many children’s authors who got their start as a staff artist for Cricket, said in an email. “She created a brilliant, engaging, positive world between the covers of her magazines.”

Ms. Sondermann met Blouke Carus, an American, at the University of Freiburg, where she was studying English literature and he was pursuing graduate work in chemistry. They wed in 1951 in Gummersbach and then moved to Paris, where they both enrolled at the Sorbonne.

Their studies were cut short when Mr. Carus’s father, who owned a company that produced both industrial chemicals and college textbooks, announced that he was going to retire and asked his son to come home to take over.

Home was LaSalle, Ill., a small town about 90 miles southwest of Chicago and a far cry from Paris and Freiburg. But Ms. Carus carved out a niche for herself, commuting to the University of Chicago to study art and German literature and raising their three children.

In addition to her daughter Inga, she is survived by her husband; another daughter, Christine Ann Carus; a son, André Carus; and four grandchildren.

The Caruses spent long stretches in Germany, and André, their oldest child, started the first grade there. When they returned, they noticed the disparity between the challenging, rich texts used in German schools and what they considered the plodding, condescending materials used in America.

In 1963 the Caruses created a series of elementary-school readers, full of advanced vocabulary and complex stories. But the books struggled to win over teachers who were more familiar with the slow-going “look-say” method of reading instruction.

“They were aghast at what Dick and Jane had done to American reading,” John Grandits, Cricket’s first designer, said in a phone interview.

The Caruses tried a different approach a decade later with Cricket, starting with their advisory board, which they stacked with literary heavyweights, among them the children’s author Lloyd Alexander; Virginia Haviland, the founder of the Children’s Book Section at the Library of Congress; and the novelist Isaac Bashevis Singer. (A story by Mr. Singer, about a cricket who lived behind a stove, inspired the magazine’s name.) The board offered advice and helped the Caruses make inroads among the librarians and well-educated parents they would target as subscribers.

The couple also drew on the East Coast literary world to build their staff. Marcia Leonard, an editorial assistant and their first hire, was a recent graduate of the publishing course at Radcliffe College. They hired Clifton Fadiman, a former books editor at The New Yorker, to be Cricket’s senior editor. Mr. Fadiman’s regular radio and television appearances made him one of the few midcentury New York intellectuals to become a household name, and he used his extensive network of friends to stock the magazine’s pages: He got his friend Charles M. Schulz, the creator of “Peanuts,” to contribute to the first issue.

Alongside Mr. Schulz, the first few issues of Cricket featured new work by Mr. Singer and Nonny Hogrogian, a two-time winner of the Caldecott Medal for children’s literature, as well as reprints of work by T.S. Eliot and Astrid Lindgren, who created Pippi Longstocking.

Writers of both children’s and adult literature tried to get into the pages of Cricket; Ms. Carus once rejected a submission by the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist William Saroyan. (He took it gracefully and sent in another story, which she accepted.)

Ms. Carus published several anthologies of Cricket stories, and in the early 1990s launched three more titles, aimed at different ages. She ran the magazine out of a book-filled warren of offices above a downtown bar, and later out of a repurposed clock factory. Around 2000 its headquarters, and its staff of about 100, moved to Chicago, though Ms. Carus, still the editor, decided to stay in LaSalle, with some of her top editors trekking back and forth every few days. The Caruses sold Cricket and its related titles in 2011; they are still being published.

Despite its fan base, Cricket never made much of a profit, a fact that did not seem to bother Ms. Carus.

“This is an idealistic undertaking,” she told The Baltimore Sun. “We’re not trying to make money. If we were, we’d be in comics and sex manuals.”

Source: Read Full Article