Amid a chaotic COVID-19 vaccine rollout, states find ways to connect shots with arms

Creating vaccine navigators. Sending letters to all seniors. Setting up 24-hour hotlines. Cold-calling people to sign them up.

States and counties are getting better at the nitty-gritty of what’s required to get COVID-19 vaccine into arms, but distribution still varies because of the nation’s fractured and underfunded health system. It’s led to broad disparities in state vaccination rates.

“This is really a function of the total chaos of 50 state health systems in an uncoordinated, unresponsive, underreported system to the federal government,” said Barry Bloom, an immunologist and former dean of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Crazy as that may be, that’s the American way.”

What’s remarkable, experts said, is how many find ways to make it work.

A look at the map of vaccine uptake shows a wide range across the USA. As of Monday, Alaska led at23% of its population vaccinated with at least one dose, followed by New Mexico at 22%. On the low end were Georgia and Utah at 12% and Alabama, Tennessee and Texas at 13%.

Vaccine tracker: Tracking COVID-19 vaccine distribution by state: How many people have been vaccinated in the USA?

There are just as many reasons for the successes as for the failures.

Leadership matters, particularly the ability to pull people together, ask hard questions and empower workers to solve problems, said Dr. Bruce Gellin, president of Global Immunization for the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

States that have done well have frequent meetingsthat include decision-makers, so there is no waiting for authorization from on high. In some cases, officials meetseveral times a day to figure out what’s working, what isn’t and what needs changing, Gellin said.

That’s been the case in West Virginia: Despite having one of the nation’s highest rates of poverty, the state has vaccinated 18% of its population and consistently has been in the top tier for immunization.

The man running its Joint Interagency Task Force for COVID-19 Vaccines, retired Maj. Gen. James Hoyer, said having support at the top is one of the secrets to his state’s success.

It began early on, when West Virginia opted out of a federal program to use CVS and Walgreens to get vaccine to nursing homes and assisted living facilities, where the majority of deaths were occurring.

More than 50% of the state’s pharmacies are independent, so large national chains wouldn’t be a good fit in West Virginia, Hoyer told Gov. Jim Justice.

“He looked me in the eye and said, ‘You believe this is the best way to protect our people?’ I said I did,” Hoyer recalled. “If the guy at the top is willing to pull the trigger and support the people who work for him, that gives us a big leg up on getting things done.”

Hoyer ends every day with two calls: one to state health officials and one with the leaders of the task force. The question he asks is simple: “What do we got to fix today?”

West Virginia also stands out for its state vaccine appointment reservation system. People 18 or older can preregister online or dial an 800 number, and they hear back with a call, email or text when it’s their turn to make an appointment.

Because it has the nation’s third-oldest population, behind Maine and Florida, and many people live in rural areas with poor internet access, the state invested $760,000 in a registration system from Everbridge. The statewide 800-number has been crucial to reaching people.

It’s been a model of efficiency compared with other states.

“We had people who wanted to talk to a real person, so we got them. I looked this morning, and we’re down to 2:30 minute wait time,” Hoyer said last week. That was down from eight minutes earlier in the month.

Contrast that with Massachusetts, where the release of COVID-19 vaccine appointments resulted in initialwait times ofmorethan 40 hours and people reporting 95,000 people ahead of them in line. By Monday, wait times were down to less than an hour, though few appointments were available.

In a White House briefing Friday, Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, acknowledged that getting vaccine out has been difficult.

“We’re doing an unprecedented thing, trying to vaccinate the entire country in a really short period of time with vaccines that providers haven’t seen in years before, vaccines that are slightly complicated,” she said. “So it’s not surprising that there have been bumps in the road.”

Smaller states tend to fare better

Flexibility and ingenuity were key for Heidi Parker, executive director of Immunize Nevada, a nonprofit group that supports immunization. In January, when vaccines became more available, call volume to the agency skyrocketed 550%.

“Obviously, that wasn’t sustainable,” Parker said, so she picked up the phone herself and found 20 collegestudents at the state’s two schools of public health to do field study placements answering calls.

“They’re going to come out of this as vaccine champions, and they’re doing a fantastic job,” Parker said.

Such hands-on approaches work well in less populated states such as Nevada, where the public health community is relatively small. The students Parker called in came from a program run by Dr. Trudy Larson, dean of the school of community health sciences at the University of Nevada-Reno in one of the state’s 16 counties.

“Can you imagine if you have 100 counties and you’re the state agency and you have to coordinate with 100 county health departments?” Larson said.

Allowing counties to tailor their approaches has helped. During the pandemic lockdown, Nye County, Nevada, put together a call list of all of its senior citizens to check in on them. When vaccinations rolled around, the county used it to call everyone and make sure they’d signed up.

There are exceptions, but in general, smaller and more rural states have fared better than many large, urban ones. For some, close contact with local health departments and a strong central system helped get the vaccine out.

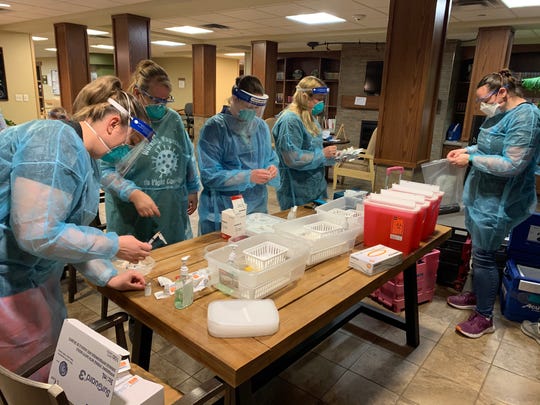

Health care workers in North Dakota prepare COVID-19 vaccines for a clinic Feb. 26. (Photo: North Dakota Department of Health)

In North Dakota, which has immunized 20% of its population, vaccine is delivered to a state warehouse wherevials are repackaged in small numbers. A courier drives them to providers who may need as few as 20 doses, said Molly Howell, immunization director for the state’s Department of Health.

Lastweek, her staff drove nine Pfizer vaccine routes that made 40 stops, delivering a total of 678 vials, containing about 3,390 doses.

“We knew people wanted to have access to as close to where they live as possible. We have 400 providers signed up, and we put them on a rotation,” she said.

North Dakota uses every available means to reach those who are eligible. Howell got the AARP chapter to send cards to everyone 65 or older and does open calls with members. Early this month, she plans to send letters to everyone over 65, just to make sure they haven’t missed anyone.

Equity vs. speed

Another major challenge for states is the need to balance equity and speed.

Most states have struggled to distribute vaccine equitably because of challenges with transportation, internet service and other social issues that make it harder for low-income people to access reservation systems and mass vaccination sites.

“You can line people up in football stadiums and vaccinate 7,000 people a day and increase your numbers. But if you’re not getting the most vulnerable populations – over 65, over 75, people with comorbidities, African Americans and Latinx – you’re not going to save that many lives,” said Bloom, the former Harvard dean.

There’s no standard public health infrastructure to identify who’s at risk, said Dr. Eric Schneider, senior vice president for policy and research at the Commonwealth Fund, a private philanthropy group that studies health care policy and practice.

“The U.S. health care system is really finely tuned to delivering health care services to people with means,” he said.

Addressing these inequities requires a tailored approach. Some residents of Santa Clara County, south of San Francisco, are highly tech-savvy and comfortable going through their health insurance company or using the internet. Others have less access and less confidence in the system.

To make sure vaccine reaches everyone, contact tracers are retrained as vaccine navigators to help people through the process of signing up to be immunized.

The navigators call people who in the past year had a possible exposure to COVID-19 to tell them when they’re eligible to get vaccinated. If they may have been exposed, they’re likely in a high-risk group, said Dr. Sarah Rudman, public health director for the Santa Clara County Public Health Department.

That effort is ramping up this week as the county broadens its vaccine eligibility group to include essential workers in child care and education, agriculture and food service and emergency services workers, Rudman said.

To ensure people in the hardest-hit communities get appointments, “we make those calls first,” she said.

“We’ve had a hugely positive response,” Rudman said.

Calling to tell people they may have been exposed to COVID-19 and need to quarantine for two weeks was never easy. The calls they make now are joyful.

“We’ve had folks who are in tears, she said, “people who never thought this day would come.”

Source: Read Full Article